SOME FAVORITE BOLLER THEATRES

![]()

Click a link to go directly to the theatre of your choice

TEXAS (SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS)

MISSOURI (ST. JOSEPH, MISSOURI)

KIMO (ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO)

UTE (COLORADO SPRINGS, COLORADO)

BROOKSIDE (KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI)

THE FABULOUS TEXAS THEATRE IN SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS - BETRAYED AND DEMOLISHED

The 3000 seat, $2,000,000 Texas Theatre at 153 E. Houston Street in San Antonio opened as part of the Publix chain on December 17, 1926 with a stage production, The Inaugural Banquet ; an orchestral and motion picture feature, Melodies of Southern States; singer Mabel Hollis; coloratura Helen York; violin solos by Irmanette ; comedian George Dayton; Publix News ; a concert on the Mighty Wurlitzer and the film feature, Kid Boots , starring Eddie Cantor and Clara Bow. The Theatre, called “a picture of Old Spain, erected upon the banks of the San Antonio River…” was a project of W.J. Lytle, a local theater pioneer, and the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation headed by Adolf Zukor and Jesse Lasky. Robert Boller himself referred to the style of this theatre as “Spanish Colonial”. It was one of the largest and most ambitious projects undertaken by the Robert Boller and the Boller firm. Billed as “an acre of seats in a palace of splendor”, it was noted for its quality and decoration in its own day in contemporary accounts in Motion Picture News Theatre Building and Equipment Buyers Guide and the compendium of modern theatre designs, American Theatres of Today . According to Robert Boller himself, the aim of Mr. Lytle in building the Texas was “to always leave them smiling when you say goodbye…”. The Texas was the site of the world premier of the film Wings on May 16, 1927 which launched the career of Gary Cooper. Later that year this film won the first Academy Award given for Best Picture.

In 1982 the Texas Historical Commission deemed the Texas eligible and recommended for listing on the National Register of Historic Places . In spite of an agreement with the city that an arts district encompassing the Texas and other historic theatres in downtown San Antonio would be established, it was decided to demolish the theatre. After a public relations battle between RepublicBank San Antonio, local labor, the architectural firm of Ford, Powell and Carson and the Mayor of San Antonio, Henry Cisneros vs. the UTSA Collegiate Preservation Society, the San Antonio Conservation Society Foundation, local and national theatre historians, architects and preservationists, and local citizens concerned with San Antonio's heritage, the Texas was demolished. The demolition was recorded in pictures, surreptitiously taken by two photographers under cover of darkness with which they produced an exhibition.

It is interesting to note that Cisneros was called in as an intermediary in this dispute, but made his feelings clear in a speech he delivered to the local Lion's Club in April, 1992 when he declared that the fight between saving the Texas vs. the building of a new bank was “not even a close call”. Citizens who sought to save the theatre included architect Killis Almond of De Lara Almond Architects, Inc. and Patrick Steele, Director of the Missouri Heritage Trust as well as numerous other architects across the country The local Conservation Society sought to restrain the bank through federal court and the application of federal Historic Preservation laws and regulations from the Comptroller of Currency concerning property activities of banks under their jurisdiction.

During this fight, the normal 120 day review period required before the demolition of an historic building which had been granted was overridden by the Mayor and City Council enabling RepublicBank to act quickly to destroy this bit of San Antonio's history, in spite of offers by the Conservation Society to buy the Texas or raise the money to save it. In a move to placate the arts community, the bank agreed to retain the façade of the Texas as a feature of the façade of the 15 story modern bank building, making it one of the most bizarre and unsettling pairings imaginable in architecture and a constant reminder of the insensitivity required to produce it. Decorations from the theater were also removed to various locations around San Antonio .

The Texas façade today on the front of the former Republic Bank

The style of the ornate Texas has been called “Cowboy-Spanish…Wild West Rococo…” Its exterior featured a three story colonnade of single and paired Composite columns that had embellished lower drums. These columns supported a polychrome terra cotta encrusted entablature in shades of Wedgwood blue, gold, red and green capped by heavy moldings.

.......

The façade and the lobby of the Texas Theatre

The auditorium

Above, a string of rectangular windows punctuated by panels with shields rested beneath another polychrome entablature and a sloping roof faced with Spanish tiles. Flanking these features were two elaborate corner pavilions faced with buff terracotta in imitation of ashlar. From a broad elliptically arched opening at street level, each pavilion rose through three stories of multi-paned windows to a polychrome frieze. Rising from this at the same level as the string of windows and shield panels, a porch with balconet and Serliana was capped with baroque gables resting beneath a larger Mission style gable with fractables and urn finials. The balance of the building was faced with buff terra cotta in imitation of ashlar masonry with additional polychrome terracotta decoration and similar pavilions at its cardinal points. A large vertical sign reading “ Texas ” topped by a star punctuated one corner pavilion. The marquees were finished in copper and hung with glass pendants and small copper bells that tinkled in the breeze.

Inside, the lobby was arranged as a patio of a hacienda beneath an open painted sky and surrounded by red tiled roofs supported by white stucco walls broken by windows with mural views behind balconets framed by awnings and grillwork. The red tiled floor was embellished with a central mosaic emblema with gold background depicting a green star enclosing a shield. Fountains in the entrance lobby were arranged with colored lighting effects reflected off their sprays. Leading to the walnut finished foyer and auditorium, turquoise colored doors with patterns formed from large brass studs pierced the white stucco walls beneath polychrome terracotta tympani. The coved arches formed by these were supported by short ornate Composite engaged pilasters. A stairway in red tile with grilled iron balustrade led to the second floor. A basement lounge was of similar finish with an added terracotta fireplace. The walls were ornamented with engaged arches enclosing mural s of typical Texas scenes of cattle drives and pioneers by colorist José Arpa (see below). A nursery equipped with attendants, sand piles and swings was provided. All these rooms were furnished with fine oak, wrought iron and marble furniture, porcelains, paintings, Spanish weaponry, tapestries and silks hangings, copper urns, antiques and even a miniature Spanish galleon.

The semi-“atmospheric” auditorium, done in shades of crimson, rose, gold and blue with a balcony and gallery, was arranged as a Spanish garden enclosed within arcades of paired spiral Composite columns on the side walls. Within these arches, colorist painter José Arpa, a student of Martin Rico and native of Seville , Spain , painted eight Texas scenes, each 16' by 25', with the two themes of contemporary Texas ranch life and the coming of the pioneers. Above, the first of the Boller canopy ceilings composed of polychrome painted plaster and wire mesh hung as if made of canvas, suspended from each engaged column on the side walls with a blue sky “atmospheric” ceiling overhead. Lighting effects creating an atmosphere of dawn, daylight or night were worked from behind this canopy. From the center of the polychrome medallion at the midpoint of the canopy was suspended an elaborate chandelier which appeared to hold dozens of long candles on a stepped brass base. The elliptically arched proscenium was flanked by draped “windows” with murals of trees capped with cartouches and angels behind balconets that rested over arched doorways embellished with polychrome tile and terracotta. Above the screens, short spiral columns in clusters supported a sounding board faced with short exposed wooden beams. The organ screens appeared as small loggias on either side of the proscenium just below the sounding board. The orchestra pit was large enough for 60 musicians and was the first in the south which could be raised and lowered, while the modern stage was equipped with the best of everything, while Carrier Manufactured Weather kept the temperature ideal. A separate gallery, mezzanine and retiring rooms were included “for colored patrons” and a cry room was provided for mothers with children who were “crying or fretful.”

AAN ART DECO WONDER - THE NEAR EASTERN ASSYRIAN/PERSIAN (AND EVEN A LITTLE SPANISH GOTHIC!) FANTASY OF THE MISSOURI THEATRE IN ST. JOSEPH, MISSOURI

The $1,000,000 Missouri Theatre at 713-721 Edmond Street in St. Joseph, Missouri, described by the local press as “a palatial temple of entertainment…” “rich in beauty and exotic daring” , opened as a silent movie and vaudeville house to an audience of 3,000 in the 1600 seat theatre with great fanfare on June 25, 1927. The program included an address by the Mayor L. V. Stigall of St. Joseph pointing to the Missouri as an example of development from outside capital that would provide jobs for local citizens ; a showing of the dramatic short based on a work by Massenet, The Elegy ; a Publix News reel; an organ solo on the $50,000 Wurlitzer Three Manual Organ by Harold J. Peterson and the feature attraction, Rough House Rosie starring Clara Bow. The show was overseen by a staff of 13 uniformed male ushers precision trained in the Publix School for Ushers in courtesy, promptness and efficiency. The Missouri was a project of Publix Theatres and Famous Players-Lasky Corporation and their Paramount Pictures on land owned by John A. Duncan, Jr. The local press noted often that St. Joseph would have a great future indeed because such important organizations had faith in the city and felt the local citizenry worthy of only the best . The design also included a two story building of offices and shops adjoining to the east which were occupied by tenants moved from another owned by Mr. Duncan. The theatre and its associated office building were seen as a stimulant to trade in St. Joseph that would enhance real estate values in the downtown area and make Edmond Street a business center by drawing out of town residents to local wholesale and retail businesses for trade as well as to the theatre for entertainment. Many of those businesses that worked on the theatre took out ads in paper on opening day pointing out their investment in the future of St. Joseph . On opening day, businesses in the building and its vicinity declared “Missouri Day Specials”, sales designed to bring shoppers and movie-goers downtown. The Boller Brothers firm is praised in the press over and over again and cited as being “among the outstanding architects in the Middle West…Their work is characterized by…real beauty…” The Missouri's Wurlitzer was sold in 1956 to an organization in Denver. But in 1970 the theatre closed and by 1972 it was slated for demolition. The Citizen's Coalition to Save the Missouri was formed under the direction of David Morton and they organized Town Hall Center, Inc. , a not-for-profit organization formed to save the theatre. This organization eventually purchased the Missouri for $125,000 with the aim of turning it over to the city after funds could be raised for its renovation. In 1977, a voter approved bond issue for $700,000 was passed by an 88% majority, raising funds for its renovation after a campaign of support stressing the importance of the proposed renovation for the revitalization of downtown. In 1978 the City of St. Joseph purchased the building, and in October, 1979 it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1980 Town Hall, Inc . joined with another organization, Community Concerts , to become the Performing Arts Association of St. Joseph to manage the Missouri and raise funds for its continued maintenance. In spite of its financial ups and downs the Missouri thrives today as a performing arts center.

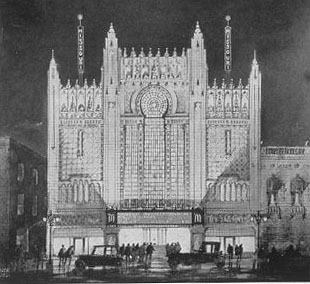

The buff terracotta faced three-bayed façade of the Missouri is embellished with red and blue enameled tile in a design that owes its character to Moorish prototypes found in Spain and North Africa .The style was termed “Spanish Gothic” at its opening, and made to resemble those of the Liberty Theatre and Lincoln Theatre both in Lincoln , Nebraska and both by the same construction firm, the J.W. Assenmachen Construction Company of Lincoln . Robert Boller remodeled the Lincoln in 1940 and its original façade design is unknown. But the Boller Brothers built the Lincoln in 1925 with a façade design nearly identical to that of the Criterion in Oklahoma City rather than to the façade of this theatre. Note that one drawing of the façade of the Missouri published in the St. Joseph News Press on September 11, 1926, page 2 shows the basic design of the theatre as constructed with the addition of a domed feature supported on horse shoe arches and placed atop the central bay.

Above the street level of corbel arched store fronts, its design is dominated by the central bay. A string of arches supported by spiral columns, two Serlianas flanking three lobed arches, act as a base for the grand horse-shoe arched central art glass multi-paned window flanked by its spandrel of tile in a checkerboard pattern and engaged pilasters encrusted with colorful tiles, forming a Moorish variation on the Palladian window. Above, floral tracery with crockets and urn finials enclosed between towers capped with quadrafrons Palladian arches topped with finials originally formed a parapet. The two flanking bays have a string of arches at their bases similar to the central bay. Above, a zone of square glazed tile is capped with a parapet of tracery and finials like that of the central bay. Towers similar to those in the central bay terminate the façade on the east and west.

Architects rendering of the exterior design of the Missouri Theatre

The two-story Missouri Theatre Building , also a Boller design, abuts the theatre to the east. Its façade is of yellow brick ornamented with buff terracotta as quoins, stringcourses and the surrounds and fanlights of its round arched windows.

The outer lobby of the Missouri is faced with colorful glazed tiles and includes utility openings outlined in tiles and capped with onion and horseshoe domes and display windows for lobby cards and posters which originally had lobed arched openings supported by columns. This outer lobby acted as a backdrop for the ornamental iron and tile box office fitted with ogival openings and embattled with corbeled pyramids created by Seaman and Schuske Sheet Metal Works of St. Joseph.

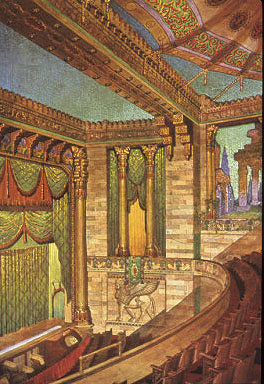

The exotic theme of the exterior is continued in the lobby and foyer with brilliantly colored soffits , molding and cornices embellished with rosettes, dentils, rinceaux, lotus and other reliefs. On the mezzanine, broad corbeled arches decorated with spirals rest on pilasters with tongue capitals and support a ceiling of stepped cornices with relief details similar to those in the lobby and foyer. This area was originally richly furnished and included a ladies' lounge, a men's smoking room and a nursery. But it is in the semi-“atmospheric” auditorium and balcony where the exotic themes of this decoration find their best expression with motives taken from Persian, Akkadian, Assyrian and other cultures of the ancient Near East executed in plaster and staff by young artist Waylande Gregory . At this time this sculptor, who was born in Baxter Springs , Kansas , was 20 years old. He was a student of Lorado Taft in Chicago and had already become known for the interior decorations of the Hotel President in Kansas City , the ornamental designs for the St. Joseph City Hall and the interior decorations for the University of Kansas-Lawrence Administration Building. In later years Gregory became internationally known for his heroic ceramic sculpture he created in a technique he invented for the New York World's Fair (“Fountain of the Atom” 1939), the Municipal Center in Washington , D.C. and other important commissions. He was also known for his ceramic busts of Hollywood stars like Dolores del Rio and Henry Fonda.

It is intriguing to speculate on the influence the designs of Bertram Goodhue, Robert Boller's favorite architect, may have had on the interior of the Missouri . His influence on Boller in relation to his Latin Vernacular style is known. Goodhue was a world traveler and liked to paint watercolors of his travels. While in the Middle East in 1902 researching Arabic architecture for a house he was to build for James Waldron Gillespie, he was inspired to paint watercolors like Persian Reminiscence depicting many of the elements, like the lamassu, the bull capitals and the fluted scrolled columns found in the Missouri.

A lamassu is a Babylonian protective demon with a bull's body, eagle's wings, and a human head. This one is to the left of the proscenium in the Missouri

As his drawings were published in 1925, Robert Boller may have seen it or some other source with the Persian watercolors depicted. In addition, it is known that the Nebraska State Capitol by Goodhue was Robert Boller's favorite piece of architecture, according to Ivan MacElwee, one of his associates. On this building, which resembles a modernized mosque with minaret, are sculptural reliefs with themes drawn from Middle Eastern art like the panel depicting “Moses Bringing the Law from Mount Sinai".Reliefs depicting rampant buffalo with fur stylized in curls drawn from Near Eastern prototypes like the royal harp from Ur (2650 B.C.) guard the north entrance to the capital building in much the same posture and position as the lamassu at the gates of Khosabad. And this entrance to the capitol itself resembles in structure the famed Ishtar Gate of Babylon. All of these works are depicted in literature of the time and were available to influence Robert Boller before he designed the Missouri . Goodhue was indeed imbued with a love for things Near Eastern that may have been passed on to one of his admirers, Robert Boller.

Opening night descriptions note that sitting in the gold, silver, turquoise and Pompeiian red auditorium was like “being seated in a large open air amphitheater, the canopied ceiling almost hiding the clouds which drift in the sky , and night clouds passing by as one looks between the large pillars on both sides of the theatre.”

The suspended plaster "tent" ceiling with clouds painted above for atmospheric effects

Another noted that the effect of the tented ceiling was “that of the sun beating down through an Arabian tent…” The plaster tented ceiling embellished with spirals, lotus and rosettes in relief seems to be hung beneath an upper ceiling painted with blue sky and billowing clouds suspended by heavy plaster ropes secured to a crenellated entablature with a buff-on-red frieze of archers and charioteers that encircles the entire auditorium inspired by narrative reliefs from the palace of Assurnasirpal at Nimrud (875 B.C.). This entablature is supported by engaged pilasters linked by a descending stepped wall and flanked by fluted columns with elaborate capitals of floral elements, spirals and rampant bulls drawn from those found in the royal audience hall of the palace of Artaxerxes II at Susa (375 B.C.). Below, another buff-on-red frieze of floral elements framed by two goats couchant , a motif similar to that found on cylinder seals from Ur (ca. 2500 B.C.) is broken by corbel arched exit doors capped with plaques depicting rampant chimera in relief like figures found on Sassanian silver of the fifth century A.D. Lighting in the recesses of these elements produces angular Art Deco shadows adding to the exotic effect.

.......

.......

Art deco light effects and Near-Eastern inspired friezes

.......

.......

An architect's rendering (left) and an actual view of the proscenium /organ screen area

From the center of the tent canopy hangs a metal and glass chandelier with onion domed lamps and grillwork of lotus, palmettes and acanthus elements welded to a frame crowned by lobed Moorish arches. Persian lanterns at floor level provided light in the aisles.

The friezes and painted openings behind the engaged colonnade begun on the side walls continue to the painted scenes of Near Eastern fantasy landscapes between the columns near the stage and culminate in the magnificent proscenium and its associated features. Here organ lofts grilled with tiles in arabesques behind rampant bull-capped fluted columns rest on a continuation of the buff-on-red frieze of goats couchant . The lofts were originally draped with green silk enriched with gold figures. A large panel depicting a lamassu in relief, based on those guarding the gates of Sargon's palace at Khorsabad (ca. 750 B.C.), stride toward the stage from its positions below each organ loft. The flat arched proscenium is supported by additional bull columns and capped by a continuation of the archer-charioteer frieze. The sounding board is recessed and painted with blue sky and clouds. Bordering it, a soffit linking the organ lofts is heavily embellished with buff-on-red reliefs depicting striding ithyphallic griffins in heraldic position fertilizing the tree of life , similar to figures seen on cylinder seals from Akkad (c. 2200 B.C.).

Additional features of the Missouri include lighting in several colors evoking at different times night, dusk and dawn; a large chorus room under the stage; six dressing rooms on three levels backstage and a $60,000 “Manufactured Weather” system by Carrier that washed the air, dried it and then heated or cooled it by refrigeration. Air ducts for this system were hidden above the canopy as they were above the similar canopy in Boller's Texas Theatre in San Antonio.

The $150,000 KiMo Theatre at

421 Central Avenue in Albuquerque, New Mexico opened September 19, 1927 with a

showing of Painting the Town starring

Glenn Tyron and Patsy Ruth Miller, Fox News and a cartoon Oswald the Lucky Rabbit; Frances Farney

at the $18,000 Wurlitzer playing Indian melodies and Indian Love Call; Haske Naswood, Navajo baritone; Margaret Well, Zuñi soprano and “sixty Indians of the Southwest in their

most impressive dances.” The Theatre was filled to its 1300 seat capacity and

was dedicated by Pablo Abeita, former governor of the

Isleta Pueblo in

The KiMo

was a project of Oreste Bachechi, a

prominent and accomplished local businessman, theatre owner and member of the

Italian community. In 1925, Bachechi went to

The Southwestern/American

Indian theme of the KiMo may be unique today in

American theatre architecture, though the Bollers

employed it in the designs of at least three other theatres that have been

demolished or completely remodeled, the Ute in Colorado Springs, the Main in

Pueblo, Colorado and the interior of the Brookside

Theatre in Kansas City, Missouri (see below for info on these theatres). The KiMo is constructed of reinforced brick faced with thick

stucco to resemble the adobe of the region. Its main façade was designed with

three bays, the central one slightly recessed. Two store fronts framed by corbeled arches flank the theatre entrance on the south at

street level separated from the theatre by pilasters embellished with colorful

glazed terra cotta tiles and capped with spiral capitals in reds and blues

resting below brown and tan curved brackets. A broad marquee rested over the

entrance. A second floor level, nine windows, three to each bay, pierce the

stucco wall, capped with spandrels of decorative glazed tiles and curved corbel

arches. Below, corbeled triangles decorate the bases

of the pilasters between the windows. Resting on the spandrels above the

windows another group of three windows rises in each bay crowned with a frieze

of ornate circular shields alternating with elaborated spindles all

accomplished in terracotta. These shields were part of the design by

Interior of the Kimo Theatre

The interior of the KiMo is a sumptuous display of American Indian motives and

colorful murals. The cream stucco walls of the lobby and mezzanine are

embellished with the murals of Carl Von Hassler

depicting the mythical Seven Cities of

Cibola, the fabled cities of gold for which the early Spanish explorers

were searching. These appear as views

“in the distance” below the decorated wooden lintel of a “porch” at mezzanine

level painted with Indian symbols. Pilasters resting on scrolled corbels and capped

with elaborate polychrome tasseled terracotta buffalo skulls (a reference to

the Buffalo Dance at Taos Pueblo) back-lit through red eyes and mouth decorate

the stanchions of this “porch”. Similar pilasters are also employed to support

the mezzanine and its wrought iron balustrade fashioned with the shapes of

birds. Exposed beams of concrete painted to resemble wood with figures of

thunderbirds, butterflies and geometric shapes cross the ceiling, and six sexagonal drum shaped copper and goat skin chandeliers hang

at intervals from square ceiling panels decorated with zigzags and other

symbols. In addition, Navajo rugs and

native pottery originally added texture and color to the lobby area.

Fire destroyed much of

the original decoration of the auditorium in the early 1960s including the

elaborate proscenium embellished with circular shields and buffalo skulls,

chandeliers in the form of Indian farewell canoes and plaster elements designed

to resemble Navajo rugs that hung flanking the stage below the organ screens

with their balconies and spindled grills. Other details in the auditorium

included an additional lit buffalo skull and shield frieze on the side walls

and an exposed beam and rafter latticed ceiling in concrete painted to resemble

wood with colorful Indian symbols and geometric patterns.

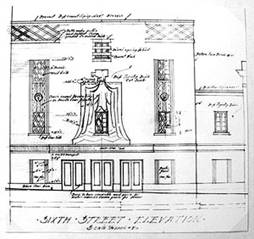

Elevation of

the Main Theatre

The 950 seat Main Theatre at 524

The original plan shows that the buff brick façade above the three pairs of entry doors was embellished with a central feature resembling an eagle with wings outstretched and head in profile to be painted on smoothed plaster in the area where cathedral windows were often found on other Boller façades. Flanking this were tall features with painted decoration inspired by Indian motives enclosed between latticed wooden grills. At cornice level, a frieze of brick laid in a lattice, termed by the architect as a “rattlesnake pattern”, rested below a flat parapet.

The interior

of the Main Theatre

Inside the decoration was simple and continued the Southwest theme. Plaster walls with ovoid arches and beams resting on corbels, all embellished with wave and diamond patterns taken from native American themes were used throughout. A lintel supported by large curved corbels capped the ovoid arch over the proscenium. Decorated exposed beams occupied the ceiling over the orchestra, and the organ screens were openings grilled with wood and capped with plaster lintels painted with chevrons. Exposed viegas done in plaster rested above the screens. The side walls of the auditorium were of plaster painted with wave and chevron patterns.

Robert Boller

built the American Indian inspired 1200 seat, $100,000 Ute Theatre at 126

The three-bayed textured stucco façade of the Ute as constructed recalled an Indian Pueblo combined with a Spanish mission and embellished with Ute symbols. This eclectic style was termed “Southwestern” by Robert Boller. The central slope-sided bay featured a balcony with a wooden balustrade and two decorated[1] wooden columns supporting a decorated wooden lintel topped with viegas of cement embellished with Indian symbols on their exposed ends. The cement panels between the columns were painted with colorful Indian scenes and symbols. A mission gable with a bell capped this bay. The flanking bays held windows closed with wooden grills, circular cement shields with Indian symbols and viegas below the flat parapet.

The semi-“atmospheric” auditorium, which included a balcony, was crowned with a ceiling of decorated beams supported by curved corbels with their lower portions tapered and lengthened to form ovoid arches. The plaster areas on the ceiling between the beams were painted as sky. Special lighting effects enhanced this illusion. Two murals in the style of muralist Thomas Hart Benton that measured 40’ in length on the side walls were focal points of the auditorium’s decoration. The west wall featured a mural of the Bear Dance, a springtime ceremony of rejoicing when the bear wakes from his winter sleep. The mural on the east wall depicted a tribe on the move heading toward the mountains. A flat lintel with painted Indian symbols capped the proscenium, and a buckskin curtain adorned with Ute symbols hung below. Flanking the stage, exit doors with adobe-like surrounds capped with Indian pottery urns rested below concentric stepped crosses painted on plaster with ventilation grills above. Circular bronze chandeliers, with cut-out forms of Indians hunting buffalo, hung from the beams and ceiling. Other features included a “powder puff room” for primping as an anteroom to the ladies lounge; a men’s lounge called the “Cowboy Room” designed by Norman Palmquist of the Boller firm and decorated with branding irons, chaps, hand carved furniture and a pair of antique longhorns; a basement lounge built around a fountain called the Old Indian Wishing Well with a plaque proclaiming, “Make a wish, lean over the well. If it bubbles, your wish will come true”; a complete stage with an orchestra pit and dressing rooms; a Grand Lounge with a fireplace and provisions for the use of television.

The interior of the Brookside

Theatre

The interior of the Georgian Revival Brookside Theatre in